My first few posts for this blog will explainer articles on Sarawak’s energy system. Note that this article is based purely on publicly available sources, and it is written from an observer’s point of view. I am not affiliated or privy to details within Sarawak Energy.

What is the Sarawak electricity grid, and why study it?

Before we introduce Sarawak’s electricity system, a good place to start is to ask why is it important to study it in the first place?

Sarawak is a region and state within the Federation of Malaysia. It is located on the Borneo island, bordering Sabah (Malaysia), Brunei and Kalimantan (Indonesia)

Malaysia’s electricity system can be divided into three separate grids: the Peninsular Malaysia grid, the Sabah (and Labuan) grid and the Sarawak grid. The East Malaysian grids (Sabah and Sarawak) are not physically connected to the Peninsular Malaysia grid. Up to recently, Sabah and Sarawak’s grid has been largely serperated, with only 30MW interconnection between Sabah and Sarawak expected to be operational in 2025. This means that these grids are physically different, with its own idiosyncracies, supply and demand profiles unique to each grid.

In electricity, more than other types of energy systems, these idiosyncracies matter. A solution that works for one grid will not necessarily work for another.

Besides that, all three grids are managed by different entities. In Peninsular Malaysia, it is managed by Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB); in Sabah and Labuan, by Sabah Electricity Sdn Bhd (SESB); and in Sarawak, by Sarawak Energy Berhad (SEB). The different governance structures means that each region may set its own priorities at each time.

I started initially studying Sarawak’s electricity grid out of personal interest, since I grew up in Sarawak. I had spent a considerable time at university trying my best to understand it. While I recognise the importance of the wider energy story for Malaysia and globally, I found it also helpful to take a local lens on certain issues. In particular, if we want to localise the wider conversations on the energy transition in practical terms or to find ways to improve, then it is understanding the idiosyncrasies in the local grid system that matters. Even within Sarawak, there are many localised issues that a Sarawak-wide discussion cannot fully address.

The aim of this article is to provide an overview of Sarawak’s current electricity system as a point of reference to support future conversations on energy in Sarawak.

Governance

Sarawak retains considerable autonomy in managing its electricity system. Its legal framework and governance structure differs from Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah.

The two main ministries setting the policy directions are under the Sarwak state government. Namely:

- The Ministry of Energy and Environmental Sustainability (MEESty) – which shapes broader energy policies, particularly those concerning environmental sustainability and renewable energy, including but not limited to just electricity.

- The Ministry of Utilities and Telecommunications (MUT) – directly regulates the electricity sector in Sarawak (alongside other utilities i.e. water and telecommunications), in accordance with the state’s regulatory framework.

MEESty and MUT are both jointly responsible for setting broader policy directions, while MUT focuses more on licensing and regulation.

Operationally, Sarawak’s electricity system is fully owned and managed by Sarawak Energy Berhad (SEB), a state-owned integrated electricity utility that provides power generation, transmission and distribution across the state. SEB, in turn, is fully owned by the Sarawak state government. SEB directly owns all the generator plants, transmission grids, distribution grids, and retail business via fully-owned subsidiaries.

Sarawak collaborates with the Federal Government on energy policies, as demonstrated by SCORE (see below). However, Sarawak retains considerable autonomy over its electricity policy, licensing and regulations. This autonomy means that while national trends significantly influence the industry, Sarawak may also set its own priorities unique to the features of its electricity system. For example, we recently see a regional push towards the hydrogen economy and energy exports in a way that may not be seen across Malaysia. Hence, while national trends give important insights, they must also be read alongside state-level positions for a full understanding of its energy direction.

The Sarawak Corridor of Renewable Energy

The most significant piece of policy that has shaped Sarawak’s electricity system today is the ‘Sarawak Corridor of Renewable Energy (SCORE)‘ policy. Launched in 2008, SCORE is a regional economic plan that intended to drive industrialisation within Sarawak by using cheap and clean hydroelectricity to attract large-scale energy-intensive industries to invest in Sarawak. Blessed with large mountainous regions, beautiful rivers, and a low population density, it is often said that the original SCORE project identified up to 20,000 MW of hydropower potential in Sarawak via 52 dams.

It should be noted that the original 20,000 MW study is not available publicly and is long outdated, so it would be wise to take this as an optimistic estimate.

Despite that, the contribution of hydroelectric dams to Sarawak thus far cannot be understated. So far, 3 dams have been built. Even with just the current 3 dams, it already makes 62% of current installed capacity and 77% of generation in Sarawak (as of 2021) [Source: MyEnergyStats]. Indeed, these developments enabled the growth of the Samalaju Industrial Park in Bintulu, which brought in new industries that had not been seen before in the state. For example, metals & smelting, advanced chemical processing, and other heavy-industry manufacturing. Headline figures indicate that SCORE has attracted RM 102 billion in industrial investments thus far, and created more than 7000 new jobs, which indicates a positive macroeconomic impact.

In this lens, Sarawak’s energy policy is also its industrial and economic policy. Sarawak’s de-facto approach to economic development since SCORE is for the Sarawak Government to utilise its ownership of SEB to construct new electricity sources (through hydro and other means), and to offer cheap electricity to sectors deemed strategic by the state government.

Nonetheless, this approach attracts large criticism for its significant environmental impact. For example, the Bakun Dam alone submerged a forest area nearly the size of Singapore. Reports also highlight the displacement of indigenous people, who reportedly have been inadequately compensated. For this reason, there has been strong opposition on continued dam building within the state.

This ongoing tension between economic growth, environmental sustainability, and indigenous rights continues to shape Sarawak’s electricity landscape today.

Sarawak’s Electricty System Today

The main features of Sarawak’s electricity system today is largely a result of SCORE.

- Supply – is heavily dominated by resevoir hydro

- Demand – is heavily dominated by large industrial users (not domestic users)

Electricity Supply

As per latest available data from MyEnergyStats (2021), 62% of installed capacity in Sarawak comes from hydro, through the Batang Ai (108 MW), Murum (944 MW) and Bakun (2400 MW) dams. The remaining capacity is from coal-powered plants (1104 MW, 18%), powered using indigenous coal, and micro-hydro/diesel generators (102 MW, 4%) used to power off-grid rural communities. The remaining ‘Private Gen’ and ‘Cogen’ capacity (which makes up a minority) comes from large industrial users privately owning their own generation plant, which are not connected to the grid.

It should be noted that under MyEnergyStats data, there looks to be a significant shift from Independent Power Producers (IPPs) to SEB ownership. However in reality the IPPs here are not really IPPs from private players in the traditional sense. Rather, the IPPs that were contracted to sell electricity to SEB were from other publicly owned companies owned by the Sarawak and/or Federal Government. By 2005, SEB had begun consolidating all these assets to streamline operations. They were all bought over by SEB to be SEB-owned subsidiaries, with the last acquisition of the Bakun Dam from the Federal government in 2017.

Electricity Demand

On the demand side, 78% of demand came from industrial sources in 2021 – this makes up the majority of the demand stack by far. By comparison, domestic and commercial demand only make up 10 and 9% of demand respectively, and their growth has been very slow over time. From 2016 onwards, 190-200 MW of capacity is reserved for electricity exports to West Kalimantan in Indonesia. We see a steady growth in demand over time, mostly driven by the growth of industrial sectors. [Source: MyEnergyStats]

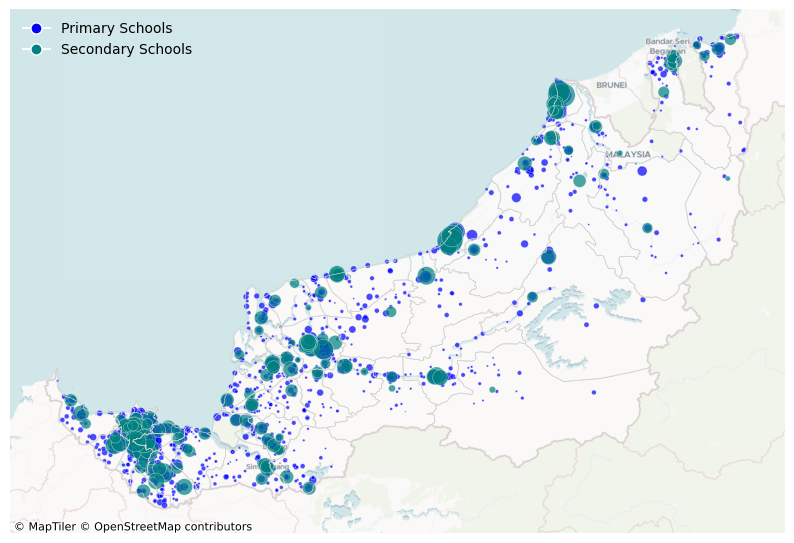

There is no granular data from which zones this demand comes from, but we can easily infer that the industrial demand mostly comes from the Samalaju Industrial Park (SIP). Reports show that much of the electricity in Bakun (and Baleh coming up in 2026) was bought by investors in SIP before the dams were built. On the other hand, the residential and commercial demand would be driven by population density, which should be concentrated in Kuching, followed by Miri, Bintulu and Sibu.

Supply and Demand Locations

A key observation from this supply-demand profile is that most of Sarawak’s demand centres are located far from the supply. Demand is concentrated along the coasts and near ports, where human activity is most abundant; while hydro supply (current and future) is concentrated in the mountainous interior of Sarawak. Besides that, there are many small townships and settlements scattered across the interiors which are particularly difficult to connect (and maintain). This means that transmission and distribution capacity as well as reliability is very important for Sarawak.

Sarawak’s electricity transmission is anchored by a 500kV transmission backbone running along the coastal areas, which connects to localised distribution grids in key regions in the South (Kuching and surrounding areas) as well as parts of the North (Bintulu, and Miri). Efforts are still underway to extend the transmission backbone to the further Northern areas (Lawas and Limbang) by 2025-2026. [Source: Sarawak Energy]

Sarawak’s Electricity System Tomorrow

With this in mind – what should the Sarawak electricity system of tomorrow look like? There are already a range of views out there, of which I can summarise into three main categories.

(1) Local Development: The current trajectory is to build more capacity to drive industrialisation. Continuing with SCORE’s original intention, it is argued that attracting investment in energy-intensive industries with cheap, clean electricity can boost economic growth and infrastructure development, such as public transport.

(2) Energy for Exports: An extension of the original intention of SCORE, Sarawak can also build more capacity to be exported to other regions. This can be via future potential interconnectors (to Singapore, Kalimantan, Brunei and Sabah), cementing its role in a future Borneo grid and ASEAN grid. It can also be exports in the form of hydrogen. This is where electricity is converted into hydrogen via electrolysis, which can be exported to as far as Japan and Korea. Rather than direct development, economic growth in this sense will be in the form of revenues to the state which must be properly redistributed.

(3) Halting Further Dam Development: Due to the significant environmental and socioeconomic impacts (which must not be overlooked), some advocate against this development model. How many more dams do we build before its enough? How much does that weigh against environmental and social cost as a trade-off? Are there pathways for development that is less-dependent on energy?

That is not to say that these views are mutually exclusive. And of course a spectrum of views exist. For a topic that so closely intertwines with the everyday lives of Sarawakians, the debate remains alive and well.

Conclusions

Sarawak has a unique electricity system – not just the sheer dominance of hydropower in its system, but also how integral it is to the economic and industrial policies of the state. It has a large impact on the day to day lives of people. For this reason, discussions surrounding its energy policies are both necessary and complex. Understanding the nuances of this system is crucial for engaging meaningfully with the many open-ended questions it poses.

As the system continues to evolve, the decisions being made today will shape Sarawak’s energy landscape for decades to come. These are questions I often reflect on, and I hope to answer them continually, with experience, as I progress with my career. I hope to write about some of these thoughts in this blog from time to time. I hope you will join me in engaging with some of these questions too.

Leave a Reply